The Tragedy of Private Property - P1

Property, as we know it, is recent. The traditional type was communal property even in England

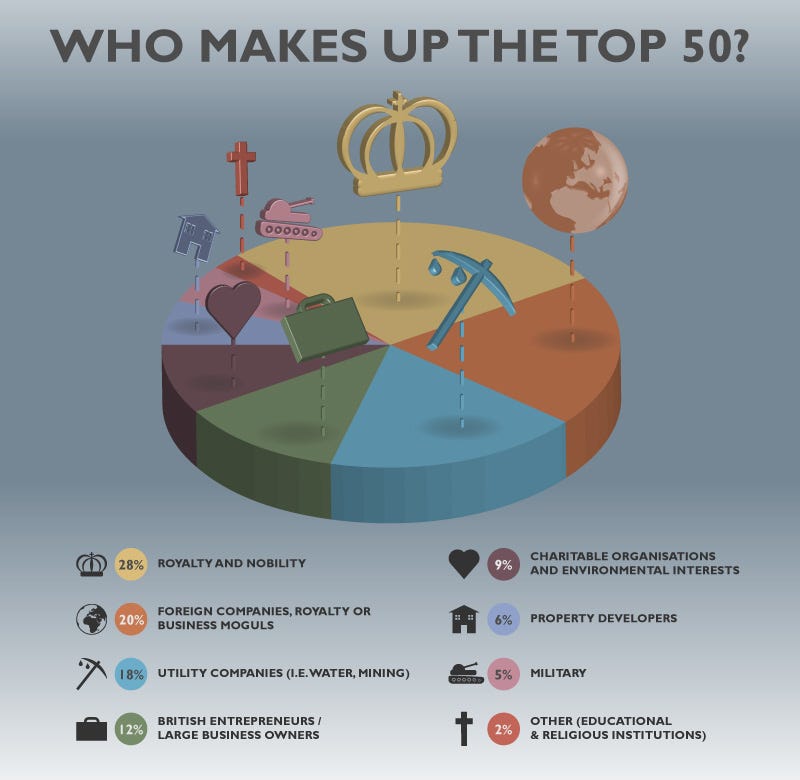

Currently, in Britain, our “property-owning democracy,” nearly half the country is owned by 40,000 land millionaires, or 0.06 per cent of the population, while most of the rest of us spend half our working lives paying off the debt on a patch of land barely large enough to accommodate a dwelling and a washing line1.

Our popular media seems to give us the impression that our current enclosed land concentration has been here forever. However, the current system of land ownership is a fairly recent development in our history.

Private ownership of land, and in particular absolute private ownership, is a modern idea, only a few hundred years old. "The idea that one man could possess all rights to one stretch of land to the exclusion of everybody else" was outside the comprehension of most tribespeople, or indeed of medieval peasants. The Lord of the Manor, held dominion over the estate, but the peasant enjoyed all sorts of so-called "usufructory" rights which enabled to graze stock, cut wood or peat, draw water, or grow crops, on various plots of land at specified times of year.

The Open-Fields

The open field system of farming, which dominated the flatter more arable central counties of England throughout the later medieval and into the modern period, is a classic common property system which can be seen in many parts of the world. The structure of the open fields system in Britain was influenced by the introduction of the caruca, a large wheeled plough, developed by the Gauls. The caruca required a larger team of oxen to pull it —as many as eight on heavy soils — and was awkward to turn around, so very long strips were ideal.

Most peasants could not afford a whole team of oxen, just one or two, so maintaining an ox team had to be a joint enterprise. Peasants would work strips of land, possibly proportionate to their investment in the ox team. The lands were farmed in either a two or three course rotation, with one year being fallow, so each peasant needed an equal number of strips in each section to maintain a constant crop year on year.

Furthermore, because the fields were grazed by the village herds when fallow, or after harvest, there was no possibility for the individual to change his style of farming: he had to do what the others were doing, when they did it, otherwise his crops would get grazed by everyone's animals. The livestock were also fed on hay from communal meadows (the distribution of hay was sometimes decided by an annual lottery for different portions of the field) and on communal pastures.

The open field system was fairly equitable, on two separate researchers, 50 years apart2, demonstrated, through studying the only remaining example of open-field farming, that a lad with no capital or land to his name could gradually build up a larger holding in the communal land:

A man may have no more than an acre or two, but he gets the full extent of them laid out in long "lands" for ploughing, with no hedgerows to reduce the effective area, and to occupy him in unprofitable labour. No sort of inclosure of the same size can be conceived which would give him equivalent facilities. Moreover he has his common rights which entitle him to graze his stock all over the 'lands' and these have a value, the equivalent of which in pasture fields would cost far more than he could afford to pay.3

In short, the common field system, rather ingeniously, made economies of scale, including use of a whopping great plough team, potentially accessible to small scale farmers.

The open fields were not restricted to any one kind of social structure or land tenure system. In England they evolved under Saxon rule and continued through the era of Norman serfdom. After the Black Death, serfdom gave way to customary land tenure known as copyhold. As the money economy advanced, this in turn gave way to leasehold. But none of these changes appeared to diminish the effectiveness of the open-fields.

Open fields were by no means restricted to England. Being a natural and reasonably equitable expression of a certain level of technology, the system was and still is found in many regions around the world. Vladimir Lenin mentions a system very similar to open-fields in “The Development of Capitalism in Russia.” According to one French historian, “it must be emphasized that in France, open fields were the agricultural system of the most modernized regions, those which Quesnay cites as regions of ‘high farming’4.

In Tigray, Ethiopia where the system is still widespread: “to avoid profiteering by ox, ox owners are obliged to first prepare the oxenless landowners’ land and then his own. The oxenless landowners in return assist by supplying feed for the animals they use to plough the land.”

Enclosures: Sheep Devouring People

However, as medieval England progressed to modernity, the open field system and the communal pastures came under attack from wealthy landowners who wanted to privatize their use. The first onslaught, during the 14th to 17th centuries, came from landowners who converted arable land over to sheep pastures. With legal support from the Statute of Merton of 1235, villages were depopulated and several hundred seem to have disappeared.

The peasantry responded with a series of ill fated revolts. In the 1381, Peasants’ Revolt, enclosure was an issue, albeit not the main one.

In Jack Cade’s rebellion of 1450 land rights were a prominent demand. By the time of Kett’s rebellion of 1549 enclosure was a main issue.

In the Captain Pouch revolts of 1604-1607, when the terms “leveller” and “digger” appeared, referring to those who levelled the ditches and fences erected by enclosers.

The first recorded written complaint against enclosure was made by a Warwickshire priest, John Rous, in his History of the Kings of England, published around 1459-86. The first complaint by a celebrity (and 500 years later it remains the most celebrated denounciation of enclosure) was by Thomas More in Utopia:

Other big names of the time weighed in with similar views: Thomas Wolsey, Hugh Latimer, William Tyndale, Lord Somerset and Francis Bacon all agreed, and even though all of these were later executed, as were Cade, Kett and Pouch (they did Celebrity Big Brother properly in those days), the Tudor and Stuart monarchs took note and introduced a number of laws and commissions which managed to keep a check on the process of enclosure. One historian concludes from the number of anti-enclosure commissions set up by Charles I that he was “the one English monarch of outstanding importance as an agrarian reformer.” But (as we shall see) Charles was not averse to carrying out enclosures of his own.

This article originally appeared in The Land: 7 Summer 2009

Beckett, J. V. 1989. A history of Laxton: England's last open-field village.

Orwin, C. S., and C. S. Orwin. The open fields.

Asselain, Jean Charles. 2011. Histoire économique de la France du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours 2 2.