Panama: Birthing A Nation Through a Canal

We recount the story of the creation of the Panama Canal and the Republic of Panama

In the build-up to World War I, many great powers fought for control over the “geopolitical chessboard.” Some of it, was informal. Some of it lead to direct war and confrontation between many of the imperial powers. In the next series of articles, we will detail some of these conflicts between the great powers that lead to “spheres of influence” that still affect many people today.

At the turn of the 20th century, many great powers were vying for control over Latin America. The idea for the Panama canal was created during this time. However, the area that is now known as Panama was under the control of the Colombian government. The US tried to negotiate a rather one-sided treaty with the Colombian government. The Colombian government refused to “play ball” with the US. Immediately, they started to fund a secessionist movement in Panama, through another hand-selected leader: Dr. Manuel Amador. They were able to succeed in balkanizing the isthmus from the Colombia in order to essentially colonize the “canal zone” for nearly 80+ years.

The length of the Panama Canal from the deep water Caribbean Sea to the deep water Pacific is approximately 50 KMs long. It was first proposed by French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, who picked the narrowest region in modern-day Panama in order to build the Canal.

French Navy Lieutenant Lucien Wyse negotiated a deal with the Colombian government, where they promised Colombia an annual payment of $25,000 flat-rate, and then 5% of the gross revenues from tolls of traffic from the Canal for the first 25 years, 6% for the next 25 years, 7% of the third 25 years and finally 8% for the final 25 years, after which the control of the Canal would revert back to Colombia.

The French company began construction, but soon, while digging for the Canal, they experienced huge bouts of Malaria which they found uncontrollable. Unfortunately, due to construction errors, they were also plagued by mudslides, and the French government refused to further finance this company. In 1899, this company declared bankruptcy. The treaty also stated that the French concession on the land would expire in 1904. This meant that anyone who wanted to build in the Panama Canal would have to negotiate with the Colombian government for new terms afterwards.

The US government approached the Colombian government, but they refused to accept the terms because it seemed excessively favorable to the US. According to the proposal, the US would set-up a six-mile wide “exclusion zone”, or the right to have exclusive property for certain hand-picked American corporations, subject to American laws. President Theodore Roosevelt balked the idea the Colombian government were not eager to participate. He said, “They are mad to get hold of the $40 million of the Frenchmen, and they want to make us a party to the gouge.”1 He further insulted the Colombian government by calling them “blackmailers”,“homicidal corruptionists,” and “cut-throats.” Finally, Roosevelt came to the conclusion that “You could no more make an agreement with the Colombian rulers than you could nail currant jelly to a wall.”2

Because the Colombian government refused to accede to essentially handing over the Canal to the US for the next century, the US Government decided to negotiate with hand-picked officials who would offer the canal to the US in accordance with the US’s terms. They approached Frenchman and future Panamanian foreign minister, Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla, who suggested that they initiate a separatist movement. According to the book, The Path Between the Seas, Bunau-Varilla convinced himself of his own moral right to “organize a revolution in Panama” for a “higher morality.”3

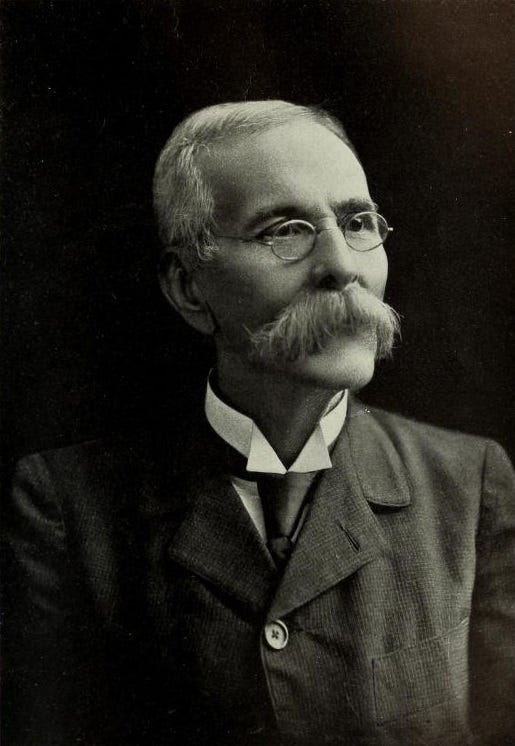

On March of 1903, American attorney, who was the attorney for the Panama Railroad Company, William Nelson Sullivan, after failed negotiations with Colombia, enlisted the help of the US ambassador to Colombia, William M. Beaupre to see if it was possible to foment a separatist movement. Mr. Beaupre recommended his friend Dr. Manuel Amador as the “leader” of the separatist movement and transferred a cable to Sullivan recommending this person. Upon this recommendation, Bunau-Varilla began acting as an intermediary between Washington and Dr. Manuel Amador.

Soon, Dr. Amador went over to the US and on September 23, 1903, at Waldof-Astoria hotel, he and Bunau-Varilla began to negotiate the terms to create the separatist movement in Panama. Dr. Amador was given money to help him raise an army to foment a separatist movement. In exchange, Amador agreed to appoint Frenchman Bunau-Varilla as the Foreign minister of the newly created independent country of Panama. Thereby, allowing Bunau-Varilla to present himself as a “legitimate” official with whom negotiations could be conducted.

Based on his air of legitimacy, Bunau-Varilla was granted an audience with President T. Roosevelt. According to accounts presented in Path Between the Seas, Bunau-Varilla claimed during the meeting, the President asked what the plan was, and to which Bunau-Varilla responded, “Mr. President, a Revolution.” To which, Roosevelt apparently responded, “A revolution!” and the entire plan was settled in the back house, smoke-filled conference rooms of Washington without consulting a single resident of the isthmus or Colombia.4

On October 15, 1903, Bunau-Varilla met with Dr. Amador again, who reiterated that he needed $6,000,00 USD to buy enough navy ships to blockade the Colombian navy from entering the isthmus. However, in this meeting, Bunau-Varilla assured Dr. Amador that he didn’t need to buy any navy ships or form a navy, as the US would help in this regards. He simply needed to pay 500 men in the newly found separatist army their salary for which $100,000 would suffice. Bunau-Varilla also assured Dr. Amador that upon secession, the US government would give him $10,000,000 for the easement in land in order to build the Panama Canal.

With this assurance, Dr. Amador embarked back to Panama, where he was busy for the next two weeks in trying to raise in army. Dr. Amador met with compatriots who had business interests that aligned with his own. Joe Augustin Arango was an attorney for the Panama Railroad company. Once in Panama, Dr. Amador was able to curry the favor of certain high-level officials through bribes and incentives. Governor of the Isthmus Jose Domingo de Obaldia was promised a cushy job in the new government. Colonel Esteban Huertas, the commander of the Colombia Battalion was placted th rough a substantial bribe and he convinced most of his officers to desert. Porfirio Varon, the police Chief of Colon, a city located at the mouth of the isthmus, was also incentivized to join the separatist movement.

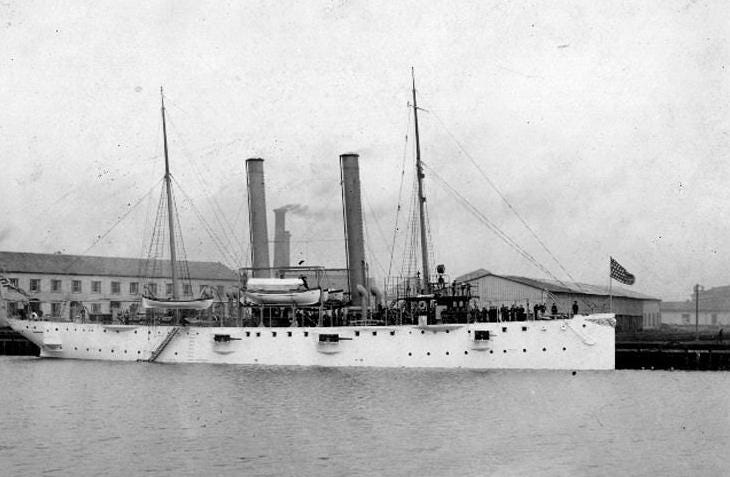

On November 3, 1903, Washington sent a telegram asking the USS Nashville, if the revolution had begun. At first, it responded negatively, but within three hours, the US engineered “revolution” for Panama would begin.

According to the website United States Foreign Policy - Peace History, here is how the rest of the “revolution” went down:

The Nashville entered the harbor of Colón in mid-afternoon on November 2. At midnight, the Colombian ship Cartagena steamed into the harbor carrying 500 troops under General Juan Tobar. There was no clash, as the Colombians were unaware of the true nature of the U.S. mission. The Colombian troops disembarked the following morning before Commander Hubbard received a directive from Secretary Darling: “Secret and confidential…. Prevent landing of any armed forced with hostile intent, either government or insurgent….” To U.S. officers also unaware of the true nature of their mission, this was a curious order, as calm prevailed across Panama. “One puzzled naval officer at Panama,” writes Schoonover, “wanted to know by what authority he should keep Colombian troops from landing on Colombian soil (in peacetime and in the absence of a civil disturbance).”

General Tobar was ready to take his troops on the train to Panama City on the morning of November 3. Railroad officials, however, devised a clever deception to separate Tobar from his troops. Encouraged by U.S. officers, Tobar and fifteen staff members made the journey across the isthmus while his troops stayed behind, waiting for a train that never came. When Tobar and his aides arrived in Panama City at 11:00 a.m., they were given a hearty welcome by Governor Obaldía and Colonel Huertas, then taken around the city to inspect fortifications and troops. Suddenly, at 5:00 p.m., Huertas’ men arrested Tobar, utterly baffled and fooled. An hour later, the insurrectos proceeded to the Cathedral Plaza and declared an independent Republic of Panama. The only violence occurred when a Colombian gunboat commander, demanding General Tobar’s release, ordered the shelling of the city for half an hour, resulting in one civilian death. A shore battery returned fire and the gunboat retreated.

Meanwhile in Colón, Colombian forces led by Colonel Eliseo Torres remained in a standoff with a smaller U.S. force backed by the Nashville’s huge guns for two days. No shots were fired. The situation was resolved when the Dixie arrived, having been delayed by mechanical problems, which made fighting out of the question for the Colombians. With the release and return of General Tobar and an $8,000 bribe paid to Torres, the Colombian troops departed aboard a British Royal Mail steamer. On November 6, 1903, U.S. Major William Murray Black was handed a new Panamanian flag to hoist over the public square in Colón amid shouts of “Viva la República!” and “Vivan los Americanos!” That same day, the Roosevelt administration recognized the new Republic of Panama.

Upon declaration of independence, Bunau-Varilla signed away the rights to the Canal in perpetuity for a twenty-mile wide concession, four offshore islands and also “any land that the US might fight necessary and convenient for the construction, maintenance, operation, sanitation and protection of the said Canal or of any auxiliary canals or other works necessary and convenient.”

US was the first country to recognize the independent state of Panama. With the cost of many lives and through great difficulty, the US succeeded in building the Canal. However, people of Panama were given the short end of the stick.

While the treaty claimed that the US government shall pay to the Republic of Panama, “the sum of ten million dollars ($10,000,000) in gold coin of the United States on the exchange of the ratification of this convention.” However, in reality, the State Department transferred the $10,000 to JP Morgan to “invest” on behalf of Panama. JP Morgan invested it in “mortgages on First Class New York City Properties” and the rest was invested in various “New York City banks” which the target rate of return was roughly .2 % points below generic corporate bonds.

Major, John. Prize Possession. Cambridge University Press, 1993. (p. 31)

Zimmermann, Warren. First Great Triumph. Macmillan, 2004. (p. 431)

McCullough, David. Path Between The Seas. Simon & Schuster, 1977 (p. 351)

Ibid (p. 353)

Hi, Esha. In your research on this canal, did you see anything on the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico? That project (or at least the idea of it) is old, too. It may or may not be relevant to your work right now but I remember reading that it was supposed to rival the Panama Canal and there was a lot of noise being made about it by AMLO along with opposition from Native folk who say they don't want or need it. It's being done for the same reasons as the proposed one in Nicaragua but with trains.

Look at: How Wall St. Created a Nation (by Espino). Some great research and detail because he had access to JP Morgan's personal library. Especially important: the role of William Nelson Cromwell and Senator Mark "Dollar" Hanna (Ohio) chair of the Republican Party. T. Roosevelt's brother-in-law was also rumored to be a member of the Morgan-Cromwell syndicate. Phillipe Bunau-Varilla's wife designed the Panamanian flag and he wasn't even a Colombian/Panamanian.