Joseph McCarthy, Red Scare and America

The Red Scare by Algorithm and remembering history before McCarthy

Yesterday, Sen. Bernie Sanders tweeted a silly, xenophobic comment about China. I also know for a fact that he does not believe the comment he made. I thought he was responding to the “red scare” mentality, a remanent of the 1960s. Leftists felt pressure to denounce communism and official enemy countries to inoculate themselves against accusations of being a communist. I tweeted out what I thought was a rather mundane tweet. I said metaphorically:

When I woke up this morning, I received a message in my inbox on Twitter saying that my account had been suspended for 11 hours because this tweet violated Twitter's terms and conditions.

After thinking about the situation: Standing up for the principle vs having my account restored, I chose the pragmatic approach and deleted the tweet. My account was restored almost a day later. One can only laugh at the absurdity of this situation. Of all my posts, the one that gets censored is the one that refers to Senator Joseph McCarthy. Because I have a historical newsletter, instead of whining about cancel culture, I will try to expand on the concept of “killing the Joseph McCarthy in your heads”

Because much of the strong labor history in the USA has been systematically erased in our text books and education, we must relearn that! To understand the true horror of the red scare, I am reprinting a piece from a 1936 publication called “Labor Defender.” Here, we learn about the alleged “un-American activities” of the communist, Angelo Herndon. This article was entitled “You cannot Kill the Working class”

In 1926 (when Angelo was 13), my brother Leo and I started off for Lexington, Ky. It was just across the border, and it had mines, and we were miner's kids. A few miles outside of Lexington, we were taken on at a clackers, which could be used only in the company store. Their prices were very high. I remember paying 30 cents a pound for pork-chops in the company store and then noticing that the butcher in town was selling them for 20 cents. The company store prices were just robbery without a pistol. The safety conditions in the mine were rotten. The escape ways were far from where we worked, and there was never enough timbering to keep the rocks from falling.

There were some bad accidents while I was there. I took all the skin off my right hand pushing a car up into the facing. The cars didn't have enough grease and there were no cross-ties just behind me to brace my feet against. That was a bit of the company's economy and the next thing I knew I had lost all the skin and a lot of the flesh off my right hand. The scars are there to this day….

Police dragging bodies after an Ohio Mining Disaster in 1930.

The Tennessee Coal and Iron Company has always been in the forefront of the fight against unions, in the South. They had-and still have-a company-union scheme, which they make a great deal out of, but which doesn't fool any of the workers. I noticed that whatever checkweighman the company put up, would always be elected.

I started surface work at the Docena mine, helping to build transformation lines, cutting the right of way for wires. I was supposed to get $2.78 a day, but there were lots of deductions.

It was while I was on this job that I first got a hint of an idea that workers could get things by organizing and sticking together. It happened this way: one of my buddies on the job was killed by a trolley wire. The shielding on that wire had been down two weeks, and the foreman had seen it down, but hadn't bothered with it. All of us surface men quit work for the day, when we saw our buddy lying burnt and still, tangled up in that wire. The next week we were called before the superintendent to whitewash the accident to the foreman and the company, so they wouldn't have to pay any insurance to the dead man's family. Something got into me, and I spoke up and said that the foreman and the whole company was to blame. The men backed me up. One of the foremen nudged me and told me to hush. He said, “It was over this grapevine that we first heard hat there were "reds" in town.”

The foremen--when they talked about it-and the newspapers, and the big-shot Negroes in Birmingham, said that the "reds" were foreigners, and Yankees, and believed in killing people, and would get us in a lot of trouble. But out of all the talk, I got a few ideas clear about the Reds. They believed in organizing and sticking together. They believed that we didn't have to have bosses on our backs. They believed that Negroes ought to have equal rights with whites. It all sounded okay to me. But I didn't meet any of the Reds for a long time.

One day in June, 1930, walking home from work, I came across some handbills put out by the Unemployment Council in Birmingham. They said: "Would you rather fight--or starve ?" They called on the workers to come to a mass meeting at 3 o'clock. Somehow I never thought of missing that meeting. I said to myself over and over: "It's war! It's war! And I might as well get into it right now!"

I got to the meeting while a white fellow was speaking. I didn't get everything he said, but this much hit me and stuck with me: that the workers could only get things by fighting for them, and that the Negro and white workers had to stick together to get results. The speaker described the conditions of the Negroes in Birmingham, and I kept saying to myself: “That's it." Then a Negro spoke from the same platform, and somehow I knew that this was what I'd been looking for all my life. At the end of the meeting I went up and gave my name. From that day to this, every minute of my life has been tied up with the workers' movement. I joined the Unemployment Council, and some weeks later the Communist Party. I read all the literature of the movement that I could get my hands on, and began to see my way more clearly.

Police Dragging an unemployed Woman in 1932 from Washington DC.

(While he was organizing the unemployment councils, he had an epiphany)

Oscar Adams, the editor of the Birmingham Reporter, a Negro paper spoke up. What he said opened my eyes-but not in the way he expected. He said we shouldn't be misled by the leaders of the Unemployment Council, that we should go politely to the white bosses and officials and ask them for what they wanted, and do as they said. Adams said: "We Negroes don't want social equality." I was furious. I said inside of myself: "Oscar Adams, we Negroes want social and every other kind of equality. There's no reason on God's green earth why we should be satisfied with anything less."

That was the end of any ideas I had that the big-shots among the recognised Negro leaders would fight for us, or really put up any struggle for equal rights. I knew that Oscar Adams and the people like him were among our worst enemies, especially dangerous because they work from inside our ranks and a lot of us get the idea that they are with us and of us.

Meeting Jim

I remember especially one white worker, a carpenter, who was one of the first people I talked to in Atlanta. He was very friendly to me. He agreed with the program, but something was holding him back from joining the Unemployment Council. He came to me one day and said that he agreed with the program but something was holding him back from joining the unemployment council.

"What's that, Jim?" I asked.

Really, though, I didn't have to ask. I knew the South, and I could guess.

"Well, I just don't figure that white folks and Negroes should mix together," he said. "It won't never do to organize them in one body.” …

"Don't you think that'll bring results, Jim?" I asked him. "Don't you see how foolish it is to go into the fight with half an army when we could have a whole one? An empty belly is a pretty punk exchange for the honor of being called a 'superior' race. As long as one foot is chained to the ground the other can't travel very far”

Jim didn't say anything more that day. I guess he went home and thought it over. He came back about a week later. It was the first time he'd ever invited me to his house, a Negro, as a friend and equal. When I got there, I found two other Negro workers that Jim had brought into the Unemployment Council. About a month later, Jim beat up a rent collector who was boarding up the house of an evicted Negro worker. He then went to work and organized a committee of whites and Negroes to see the mayor about the case. There he said, "Today, it's the black worker to see the mayor about the case. Tomorrow it'll be me," Jim told the mayor.

There are a lot of Jims today, all over the South

…

We organized a number of block committees of the Unemployment Councils, and got rent and relief for a large number of families. We agitated endlessly for unemployment insurance.

In the middle of June, 1932, the state closed down all the relief stations. A drive was organized to send all the jobless to the farms. We gave out leaflets calling for a mass demonstration at the courthouse to demand that the relief be continued. About 1000 workers came, 600 of them white. We told the commissioners we didn't intend to starve. We reminded them that $800,000 had been collected in the Community Chest drive. The commissioners said there wasn't a cent to be had. But the very next day the commission voted $6,000 for relief to the jobless!

An unemployment council session from 1933.

I want to describe the conditions of the Atlanla workers, because that will give some idea of why the Georgia bosses find it necessary to sentence workers' organizers to the chaingang. I couldn't say how many workers were unemployed- the officials keep this information carefully hidden. It was admitted that 25,000 families, out of 150,000 population. In the factories, the wages were little higher than the amount of relief doled out to the unemployed. The conditions of the Southern textile workers is known to te extremeiy bad, but Atlanta has mills that even the Southern papers talk about it as "sore spots." There, and in the Piedmont and other textile plants, young girls worked for $6 and even less a week, slaving long hours in ancient, unsanitary buildings….

Other “Un-American” demands: Free milk for Children

On the night of July 11, I went to the Post Office to get my mail. I felt myself grabbed from behind and turned to see a police officer. I was placed in a ceil, and was shown a large electric chair, and told to spill everything I knew about the movement. I refused to talk, and was held incommunicado for eleven days. Finally, I smuggled out a letter through another prisoner, and the International Labor Defense got on the job.

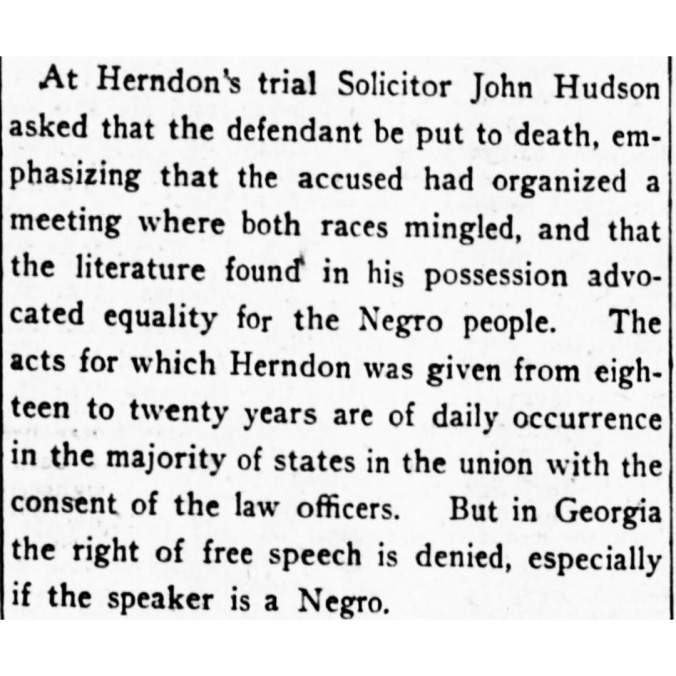

The Assistant Solicitor John Hudson rigged up the charge against me. It was the charge of "inciting to insurrection." It was based on an old statute passed in 1861, when the Negro people were still chattel slaves, and the white masters needed a law to crush slave insurrection and kill those found giving aid to the slaves. The statute read:

If any person, be in any manner instrumental in bringing, introducing or circulating within the state any printed or written paper, pamphlet, or circular for the purpose of exciting insurrection, revolt, conspiracy or resistance on the part of slaves, Negroes or free persons of color in this state, he shall be guilty of high misdemeanor which is punishable by death.

The trial was set for January 16, 1933. The state of Georgia displayed the literature that had been taken from my room, and read passages of it to the jury. They questioned me in great detail:

Did I believe that the bosses and government ought to pay insurance to unemployed workers? Did I believe that the Negro should have complete equality with white people?

Did I believe in the demand for the self-determination of the Black Belt?

Did I feel that the working-class could run the mills and mines and government

That it wasn't necessary to have bosses at all ?

I told them I believed all of that-and more. The courtroom was packed to suffocation. Attorneys, Benjamin J. Davis, Jr., and John H. Geer, two young Negroes--and I myself-fought every step of the way. We were not really talking to that judge, nor to those prosecutors, whose questions we were answering. We talked to the white and Negro workers who sat on the benches, watching, listening and learning….

The state held that my membership in the Communist Party, my possession of Communist literature, was enough to send me to the electric chair. They said to the jury: "Stamp this damnable thing out now with a conviction that automatically carries with it a penalty of electrocution."

And the hand-picked lily-white jury responded: "We, the jury, find the defendant guilty as charged, but recommend that merey be shown and fix his sentence at from 18 to 20 years."

I had organized starving workers to demand bread, aad I was sentenced to live out my years on the chain-gang for it. But I knew that the movement itself would not stop. I spoke to the court and said “You may succeed in killing one, two, even a score of working-class organizers. But you cannot kill the working class.”

Angelo Herendon was put in a draconian prison in Georgia for four years, while the ILD sold stamps all around the word to crowdfund his legal defense fund. But, the prison conditions were truly horrifying.

Accompanying Caption: An investigator gets a sample of chain-gang torture. The prisoner's legs are locked into stocks. His hands are tied behind him. He must stand in this position for hours because the chain around his neck is fastened to the floor.

Accompanying Caption: Wilson Shropshire whose torture on a North Carolina chain gang is described in this article. His feet were amputated after days of neglect in the hospital. ANGELO HERNDON MUST BE SAVED FROM THIS FATE.

An ILD poster that was spread around the world:

Angelo was eventually freed by the Supreme Court in 1937 after a series of appeals.

I also spoke last week on Katie Halper’s Show about Unemployment Unions

Other news: I will be speaking at the Move to Amend People’s Assembly on why we need a new constitution! If you are able to, please check it out. I will also be reading part of the Supreme Court Decision for Angelo Herndon to explain why we absolutely need people’s constitution.

Good piece, amazing how the mistreatment and degradation of labor gets ignored and diminished by all, right/left, black, white, green, blue u name it. The nature of capitalism, whether in poverty or prosperity, is to drive wages to subsistence levels.

Wow. Thank you, Esha, for reprinting this piece. The writing is so strong & simple & real -- you can see that mine, that crowded courtroom.

It occurs to me that simply reprinting a shitload of these old Communist articles from the '30s and '40s would go a long way to clarifying for Americans just what an effective labour movement and political movement is all about.

I was very impressed with a podcast of yours I heard just today, an interview with Alexandr Buzgalin, where he said this problem -- of even visualizing, let alone enacting, a viable Left is a problem not just in the USA or Canada (my own home country), not even just in the UK, Germany or Italy (where I live), but even in the east of Europe, where people resent and resist in small ways the attacks from the demagogic Right, but still can't pull together into an effective movement for fundamental social change