The Shoemaker of Stalingrad

While I was researching another topic, I stumbled upon this article written in 1945 by Jewish journalist, actor, screenwriter, fiction writer and war correspondent Yevgeny Krieger. He died in 1983 at the age of 77.

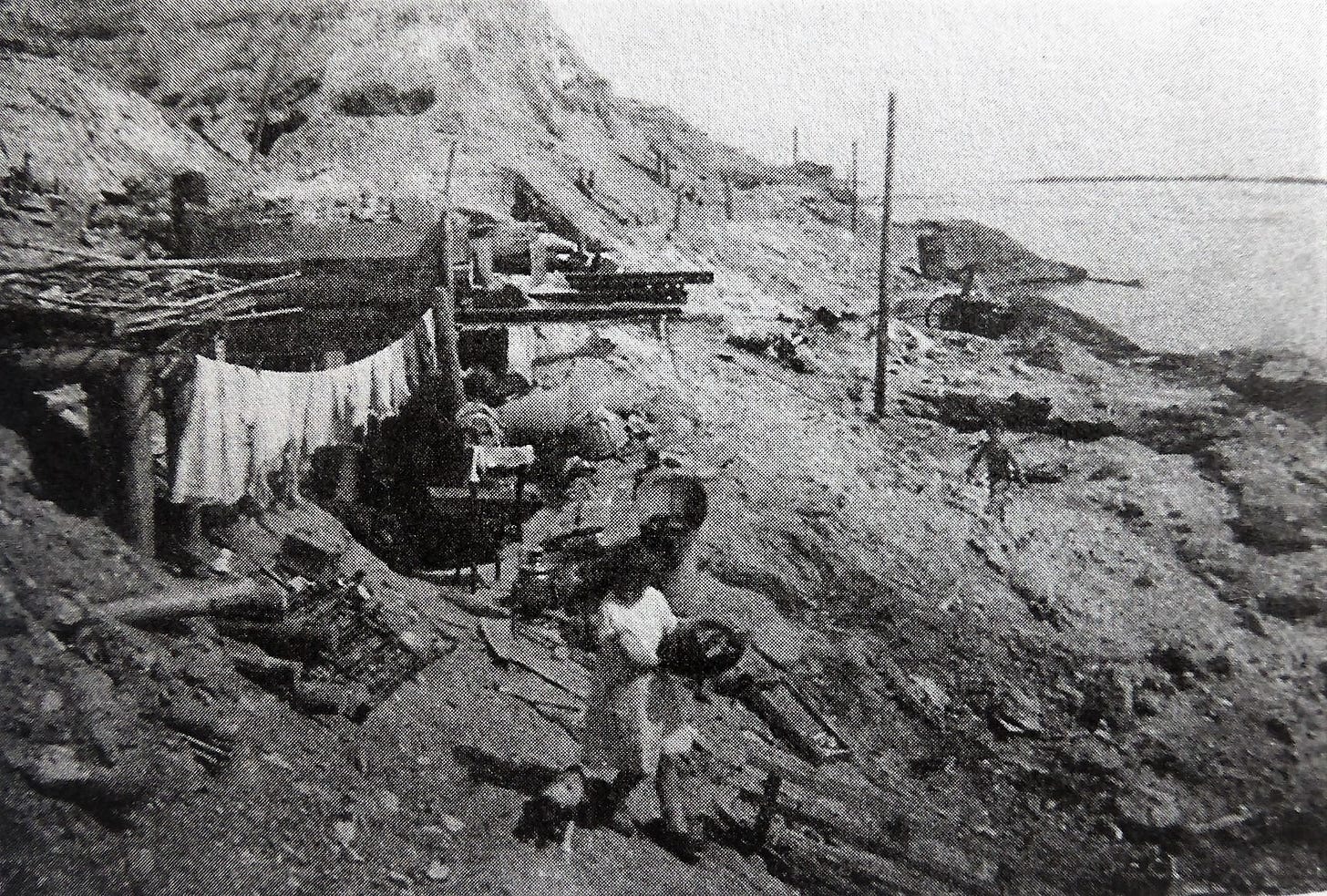

I am reprinting his article, “The Shoemaker of Stalingrad” because it touched me. I also went through the photo archives from the Battle of Stalingrad. I can confirm that there was a shoemaker there in 1943. Whether or not it is the same shoemaker, I do not know.

Battle of Stalingrad

Stalingrad was very important because the Wehrmacht because the city was on the bank of the Volga river. The Wehrmacht needed the fuel other side of the black sea. Baku was known of its oil fields.

The strategy was simple, as it was laid out by Field Marshall Reichenau:

He gave the soldiers two simple tasks:

After the Nazi surrender in Stalingrad, Yevgeny Krieger interviewed a shoemaker.

The Shoemaker of Stalingrad

I met him among the ruins of Stalingrad in 1943. My boots needed mending, and I had a hard job finding his workshop. It was in a pit, under a pile of stones and a ruined staircase.

After he had examined the soles and agreed to replace them, we talked a while, and he offered to show me where he had lived during the most terrible days of the defense. It was on a steep, precipitous bank of the Volga. The heights and tall buildings that towered on three sides were all in German hands. The Red Army was holding out on a few yards of river bank, with the Volga at their backs. The crossing was under machine gun and artillery fire. It was the last defense line of all.

The level plateau on which I stood with the shoemaker, and which was now strewn with bricks and rubbish, had once been part of a pleasant suburb. But there was not a wall standing.

"I lived here with my daughter," the old man said. "Our house used to stand just here. There's nothing left of it now, of course. When it was destroyed we moved into a bomb crater. Come over here and I'll show you. You'll have to kneel down and crawl, I'm afraid. Carefully, now! Are you all right? Well, here we are! Home at last!"

It was dark—not really dark, just gloomy. The crater was roughly roofed in with boards covered with earth. I peered about. There was a bed, a little table with some crockery on it, a kerosene heater, shoemaker's tools, and a doll. A bunch of brightly colored paper flowers was thrust into a crack in the earthen wall, over the bed

A thin, quiet little girl—she must have been about eleven years old—was sitting on the edge of the bed. When she spoke,I noticed that she had a slight stammer. "We all got shell-shocked—my little girl and I, and the soldiers too,” the old man explained. "The only way we could get anywhere was by crawling. The Germans could see everything we did."

“Our mortar gunners had their trenches practically next door, and the Germans were only 200 yards away. Oil tanks were burning all around us.”

"Couldn't you have got away to the far bank?" I asked. "Was it necessary for you to stay?"

"Well, perhaps I could have got away,” he mused. “But I'd lived here all my life, and somehow I just didn't believe the Germans would get as far as my place.”

"But it wasn't so bad, really,” he said. “The Red Army men were so cheerful. We felt quite at home with them, my girl and I. They'd crawl down to us, all black and deafened by the bombardment, and she'd make tea for us all.”

“When I was badly shell-shocked they came and looked after me, and got me right again. They were good lads. They used to make the girl laugh at their jokes and stories. They cheered her up.

“When we were asked to go away to the opposite bank, she cried so much that there was nothing for it but to stay.

“The worst time was after that—when the Germans were preparing their biggest attack. Our men could not possibly retreat. I don't remember much about the day of the attack, because we were stunned. It seemed as though the earth itself had cracked. But as you know, our men held on.

"When after the battle the commander saw me and my little girl he was astounded. He said, ‘You don't mean to say you stayed here with that child?'

“My little girl was quite frightened by his look. So she offered him some tea to calm him down. Then he picked her up and put her on his knee and began to laugh until the tears ran down his face. Perhaps he was crying, not laughing. I couldn't quite make out”

It was by ignoring the horror of what was unspeakably horrible that Russia held on in that early hell of defense. Russia took the danger as easily and quietly as the shoemaker and his daughter, in the crater on the Volga bank

At the beginning of the war, when the Russian people were using homemade incendiary bottles to stop tanks, they made fun of the whole business as they stepped out to certain death. They were not inclined to dramatize themselves.

It was in those days that the pilots who had run out of ammunition started the ramming technique. The first perished along with the enemy. Those who came after, while honoring the pioneers’ supreme courage, learned to employ ramming tactics with such skill that they could smash the enemies’ propellers while keeping their own plane intact.

Among Russian soldiers, the brave exploit of one becomes a rule for all. That is why the level of sheer heroism reached such a stupendous height as the war progressed.

I remember the dread of encirclement during the first months of the war. Yet somehow units found their way out, fighting their way across scores and sometimes hundreds of miles. Before long, encirclement maneuvers were studied as one of the regular methods of fighting. Big formations purposely went into "encirclement,” broke through the enemy front, spent weeks on end in the German rear.

That is characteristic of the Red Army—the knack of making the heroic example part of the system of fighting.

In spite of their organization and exactitude, the Germans learned nothing during the war, and finally fell victim to their own hackneyed pattern. In the last phase of the war every person in the Red Army, from the youngest platoon commander to the Chief of the General Staff, had learned to outwit the German.

In battle, Russians display a dazzling inventiveness and boldness of thought that the Germans would regard as sheer foolhardines

Behind the outflanking of all East Prussia by Marshal Rokossovsky's troops, behind Marshal Zhukov's break-through from the interior of Poland to Berlin, lay all the experience amassed since June 22, 1941, by every soldier of the Red Army, and the simple staunchness of the shoemaker of Stalingrad

A beautiful article - thank you.