Myth Debunked: Communism Works in Theory...

Debunking the tired old Myth that "Communism works in Theory and Not in Practice"

Talking Point: “Communism/socialism sounds good on paper, but it doesn’t work in the real world. It goes against human nature. It’s a nice theory that always fails in practice.”

Summary:

This is perhaps the single-most common dismissal used by capitalists against socialist governments. This is repeated ubiquitously against across all capitalist and conservative sources as an Axiom. This aphorism appears in countless forms but rarely with specific attribution - it’s treated as received wisdom that needs no justification. The argument implies that:

The theory is internally consistent and appealing,

BUT human nature or practical realities make it impossible,

Every attempt has failed, proving it can’t work,

Advocates are naive idealists ignoring reality.

Variants:

“Real communism has never been tried” (mockery of defenders)

“It’s utopian thinking”

“Sounds good, doesn’t work”

“Nice idea, wrong species”

“Human nature makes it impossible”

“You can’t change human nature”

The rhetorical function allows the person making the argument seem reasonable (”I understand the appeal...”) while dismissing the actual counterpoint entirely. Positions capitalism as “realistic” and “practical” vs. socialism as “idealistic” and “theoretical.” It frames issue as settled empirical fact rather than debatable question and it functions as a thought-stopping cliché that ends discussion before it begins.

Sources:

Pervasive across Cato Institute, Mises Institute, TPUSA, PragerU materials

Repeated by Milton Friedman, Thomas Sowell, and other prominent conservatives

Standard conservative talking point found in political discourse, social media, and casual conversation

Hoover Institution: “The False Appeal of Socialism” (2020)

Frequently cited without attribution as “common knowledge”

The genius (and weakness) of this argument is that it’s designed to be unattributable - it masquerades as universal wisdom rather than ideological propaganda.

Rebuttal

CAPITALISM DOESN’T EVEN WORK IN THEORY!

This argument is designed to masquerade as universal wisdom instead of an ideological propaganda. “It’s repeated everywhere precisely because it’s a thought-stopping cliché, not an actual analysis.” Everyone who makes this argument always advocate for another system: Capitalism.

It is meant to paint defenders of socialism and communism as idealists living in a utopian society while defenders of capitalism are painted as “realists” who understand the inner workings of the real world. However, nothing can be further from the truth.

While these anti-communists do concede to the fact that communism works in theory, they seem to forget that capitalism, doesn’t even work in theory, let alone in practice.

Why Capitalism Fails in Theory:

Contrary to popular belief, capitalism isn’t when people sell “things” or commodities, which is basically a thing of value that can be traded. Traditionally, people used money to buy commodities such as sugar or rice, and the majority would then consume most of it. However, around the 1600s something changed:industrialization. Commodities that were locally produced and sold, were now produced on a mass scale and sold non-locally in mass quantities. People who were already wealthy were able to use their money in order to trade for commodities in large quantities, not to use or acquire these commodities, but to resell it in order to acquire surplus value. Marx labeled this process the M-C-M’ cycle:

For example, if someone invests €100,000 to buy five cars and register them for ride-sharing services like Uber, the cars are not purchased for personal transportation, rather they are bought as capital. Drivers are hired to operated them. The cars are kept on the roads as much as possible. After a year, the entrepreneur has earned €160,000 in fares and commissions. This is the classic M–C–M′ cycle in modern form:

M (Money): €100,000 capital outlay

C (Commodity): Cars, app registrations, and labor time

M′ (More Money): €160,000 — the original sum plus surplus value extracted through the drivers’ work

The point isn’t that society gains more mobility — the cars’ use-value — but that money has returned to its owner augmented. The drivers’ labor and the vehicles’ wear are just the intermediaries through which money begets more money.

In Marx’s analysis, this raised a crucial question: where does that “more money” actually come from? It cannot come from the mere act of exchange, since every trade in a market swaps equivalents — €1,000 worth of goods for €1,000 in cash. The capitalist doesn’t create new value by buying and selling alone. To find the source of profit, Marx followed the chain backward and found it in the one place where something new is produced: the worker’s labor. The capitalist purchases labor power for less than the value it creates. The difference between what the worker is paid and the value their labor adds to the final product is the surplus value — and this, Marx argued, is where exploitation truly begins.

Which begets the first contradiction of capitalism: there’s only so much you can squeeze workers’ wages before the system begins to undermine itself. The more labor is exploited to maximize profit, the fewer people there are with the purchasing power to buy what capitalism produces. In other words, by impoverishing its own consumers, capital saws off the very branch it sits on. This creates a crisis of underconsumption. Capitalism ends up undermining its own market base.

The second way capitalism fails theoretically is that if there are multiple firms that produce the same commodity, each firm must expand their output to flush the competition out of business. But, when all the firms end up doing that simultaneously, the market becomes saturated and the price of the goods drop exponentially. This leads to periodic cycles of bankruptcies, layoffs and and boom and bust cycles. Many of which, we have witnessed in our lifetimes (depending on our age).

During these recurring crises, weaker firms collapse while stronger ones buy up their competitors. This process leads to the consolidation of ownership — both horizontally, when companies absorb rivals within the same industry, and vertically, when they expand control up and down the supply chain. Over time, this turns competitive markets into a handful of monopolies and cartels, exactly as Lenin described in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. What begins as a system of competition ends as a hierarchy of concentrated power.

As Lenin demonstrated in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, by 1907 just 0.9% of German enterprises controlled over half of all industrial workers and the majority of total output. What Marx had theorized as the concentration of capital had already become measurable reality.

Unfortunately, the contradictions and pitfalls don’t end there. As a handful of cartels and monopolies dominate production, their need for profit and raw materials grows insatiable. To keep their factories running and capital expanding, they must look beyond their own borders. Hence begins the drive to colonize the world — to seize new territories, control resources, and secure cheap labor. To keep their factories running and profits rising, they expand outward — colonizing the world. Colonialism reconfigured entire societies for extraction: in India, the British East India Company replaced food crops with tea, opium, and indigo; in Cuba, only sugar could be grown; in Rwanda, fertile farmland was seized for industrial coffee under German and Belgian rule. The result was the same everywhere — famine, dependence, and the destruction of local industry. Colonies that had once fed themselves were forced to import basic food from the imperial core, enriching the same corporations that had robbed them.

As Lenin explained in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, German enterprises entered the colonial race late. By the early 20th century, Britain and France had already divided most of the globe into their own spheres of exploitation. To secure access to raw materials and markets essential for its survival, German capital had only one option left — to seize colonies by force. Thus, imperial rivalry transformed into military conflict, culminating in the First World War: a struggle not of nations, but of capitalist powers fighting over a world that had already been divided.

Capitalism Fails in Practice

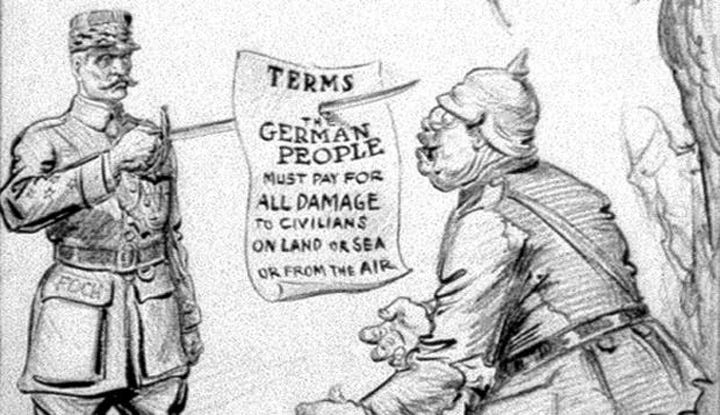

When the First World War ended, the map of empire changed, but its logic remained. The victors didn’t simply punish Germany for aggression — they neutralized an economic competitor. The Treaty of Versailles makes perfect sense when viewed through the lens of capitalist rivalry, not morality. France and Britain sought to permanently weaken Germany’s industrial base, which by 1914 had already surpassed both in steel production, chemical research, and machine manufacturing.

By stripping Germany of its colonies, restricting its military, seizing patents, and imposing astronomical reparations, the Allies ensured that German capital could not re-enter global markets as an equal competitor. Versailles wasn’t about peace; it was about market control. It froze the world’s hierarchy of production — guaranteeing that France and Britain would continue extracting from their colonies while German capital was deliberately handicapped.

The tragedy of Weimar Germany was not that fascism overpowered democracy, but that centrism surrendered to it. The ruling class, terrified of socialism and unwilling to sacrifice profits, preferred to dismantle democracy rather than risk redistribution. By the early 1930s, parliament had already hollowed itself out through emergency decrees, wage cuts, and deference to capital. Hitler did not overthrow the system; he inherited it.

As I wrote in The Economy of Evil, fascism did not emerge from chaos or irrationality. It was a rational response of a ruling class cornered by its own contradictions. When capitalism could no longer rule by consent, it ruled by coercion. Fascism became the mechanism through which industrialists preserved their property, destroyed unions, and restructured production under the guise of national renewal.

Parenti called it “capitalism in extremis” — the system defending itself with violence when ideology and markets fail. What began as economic crisis under Hindenburg and Brüning matured into political extermination under Hitler. Capital’s contradictions had finally produced their ultimate form: a state that openly fuses corporate, military, and nationalist power to annihilate class opposition.

In the end, the familiar refrain that “communism works only in theory but fails in practice” collapses under scrutiny, because capitalism has failed on both counts. Its theoretical foundations — competition, equilibrium, self-regulation — implode the moment they are practiced. Each stage of capitalist “progress” has revealed a deeper contradiction: the wage squeeze that undermines consumption, the overproduction that destroys markets, the imperial expansion that breeds world wars, and finally, the fascist synthesis that fuses capital with the state. These are not accidents of mismanagement but the logical outcomes of a system that can sustain itself only through crisis, conquest, and coercion. History’s lesson is not that communism failed to live up to its ideals — it is that capitalism inevitably lives down to its own.

Check out all the other arguments as I build the talking points:

A great answer to all the sceptics who parrot the usual responses.

You have taken on capitalism and shown how its inherent contradictions lead inevitably to crisis and violence.

This explains so much very clearly. Thank you!