But, But, Who will Protect Us from Serial Killers?

Legally, no, the Police have no Duty to Protect and Serve

Editor’s Note: Keo Keopong from Barnes Law wrote Part 1 of this article. The original article can be found here

Part 1: Protect and Serve

“To Protect and to Serve” – the ubiquitous creed emblazoned across millions of police cars throughout Los Angeles and indeed the United States. This motto is consistent with the common belief that police officers as well as other law enforcement officers are here to protect us. After all, we are all taught to dial 9-1-1 when we need help. Subject to narrow exceptions, the United States Constitution does not require law enforcement officers to protect you from other people, according to the U.S. Supreme Court. This notion contradicts our engrained perceptions, but it’s still the law today.

In the 1989 landmark case of DeShaney v. Winnebago County Department of Social Services, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the failure by government workers to protect someone (even 4-year-old Joshua DeShaney) from physical violence or harm from another person (his father) did not breach any substantive constitutional duty. In this case, Joshua’s mother sued the Winnebago County Department of Social Services, alleging it deprived Joshua of his "liberty interest in bodily integrity, in violation of his rights under the substantive component of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause, by failing to intervene to protect him against his father's violence.” While the Department took various steps to protect Joshua after receiving numerous complaints of the abuse, the Department took no actions to remove Joshua from his father's custody. Joshua became comatose and extremely retarded due to traumatic head injuries inflicted by his father who physically beat him over a long period of time.

Nevertheless, the Court found that the government had no affirmative duty to protect any person, even a child, from harm by another person. “Nothing in the language of the Due Process Clause itself requires the State to protect the life, liberty, and property of its citizens against invasion by private actors," stated Chief Justice Rehnquist for the majority, "even where such aid may be necessary to secure life, liberty, or property interests of which the government itself may not deprive the individual" without “due process of the law.”

The DeShaney decision has been cited by many courts across the nation and reaffirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court. Namely—on June 27, 2005, in Castle Rock v. Gonzales, the U.S. Supreme Court again ruled that the police did not have a constitutional duty to protect a person from harm. The decision overturned a federal appeals court ruling which permitted a lawsuit against the town of Castle Rock for the police’s failure to respond after Jessica Gonzales tried to get the police to arrest her estranged husband Simon Gonzales for kidnapping their three daughters (ages 7, 8, and 10) while they were playing outside, in violation of a court-issued protective order. After Simon called to tell Jessica where they were at (in Denver at an amusement park), for hours she pleaded for the police to arrest Simon. But, the police failed to act before Simon showed up at the police department and started shooting inside, and with the bodies of the 3 children in the trunk of his car.

In her suit against the town, Jessica argued that the protective order stating “you shall arrest” or issue a warrant for arrest of a violator and that it gave her a “property interest” within the meaning of the 14th Amendment’s Due Process guarantees, which prohibits the deprivation of property without due process. By framing their case as one of procedural Due Process and not of substance, Jessica and her lawyers had hoped to get around the 1989 DeShaney precedent. To no avail, the U.S. Supreme Court saw little difference between this case and the DeShaney case. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority, stated that Ms. Gonzales did not have a "property interest" in enforcing the restraining order and that "such a right would not, of course, resemble any traditional conception of property." The Court went on to reaffirm the DeShaney ruling that there is no affirmative right to aid by the government or the police found in the U.S. Constitution, and thus no legal recourse could be brought thereunder. The “no duty to protect” rule remains unwavering and the law today.

Needless to say, the stories of Joshua DeShaney and Jessica Gonzales’ three daughters (and countless similar stories) are saddening, and the rulings seem to be at odds with our common and fundamental understanding that the police are here to ensure our safety and provide protection. One need only look to the door of a Los Angeles police cruiser to find those reassuring words. However, those words are misleading in light of these Supreme Court rulings.

Though alarming, we simply have no affirmative right to police aid, even when a person, including a helpless child, faces imminent danger.

One of the most egregious illustrations of police having no duty to protect and serve comes from 1991.

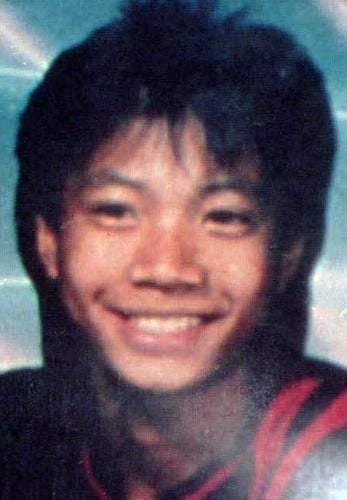

Part 2: Jeffrey Dahmer and Sinthasomphone

On the night of May 27, 1991, Sandra Smith and Nicole Childress, two young black women in Milwaukee, spotted 14-year-old Konerak Sinthasomphone stumbling on the street. Smith walked towards him to assist him. He was completely naked. He had bruises on his shoulders, legs, and knees. As Sandra Smith came closer, she saw a stream of blood running down his thigh from his rectum. Sandra Smith held the boy, but he was unable to speak. She turned to her cousin Nicole Childress and instructed her to call the police for help. Childress ran to a telephone booth and dialed 911.

The dispatcher alerted two officers, Joseph Gabrish and John Balcerzak, who were working the beat that night. The dispatcher said, "36, you got a man down. Caller states there's a man badly beaten and is wearing no clothes, lying in the street. 2-5 and State. Anonymous female caller. Ambulance sent."

Meanwhile, as Childress ran back from the telephone booth towards Smith, she spotted a tall, thin, white man carrying a six-pack of beer under his arms. He was conversing with Smith. Dahmer was trying to tell Smith that the boy was his boyfriend and was visiting from China. Smith did not believe his story.

The ambulance arrived before the police. The paramedic was a young woman who had just graduated from her training. She was a new hire who was still in the probationary period at work. She covered Sinthasomphone with a blanket as he sat on the floor in front of the ambulance.

As the ambulance began examining Sinthasomphone, the two officers arrived on the scene. They decided to split up. Officer Gabrish questioned Sinthasomphone, while officer Balcerzak questioned Dahmer. Earlier that night, Dahmer had heavily drugged Sinthasomphone, drilled a hole in his head, and covered it with acid. Sinthasomphone was unable to speak. Officer Gabrish just assumed he was drunk and couldn't speak English.

Meanwhile, Jeffrey Dahmer started to manipulate Officer Balcerzak. He feigned sincerity and said, "Look, we've been drinking Jack Daniel's, and I'm afraid he's had too much."

Officer Balcerzak asked, "How old is the boy?"

Dahmer answered coyly, "19. We live together, right here at [his address]. We're boyfriends if you know what I mean."

At this point, Childress interrupted and yelled, "look at the boy! He is either twelve or thirteen."

Officer Balcerzak yelled at Childress and told her to "Butt out." He ordered them to be quiet and threatened to arrest them on charges of interfering with an investigation if they didn't obey his orders.

Later, Sandra Smith lamented that the policemen never took their statements or showed any interest in what they had to say. Since Childress and Smith were the ones who called the police, police protocol would require them to take their statements. Instead, as Smith later testified, "We tried to give the policemen our story. I couldn't understand why he didn't want our names."

Balcerzak believed Dahmer's story. They called off the paramedic. She protested and reiterated that Sinthasomphone needed medical attention. But she was on her probationary period, and disobeying an officer would have severe consequences for her career. The officers repeated that there wasn't a real problem. Balcerzak told her, "it's a gay thing" and told her to leave. She obeyed and left Sinthasomphone in the custody of the two police officers. Later, in the trial, she testified she would have taken Sinthasomphone a hospital.

The police calmly escorted Sinthasomphone back to Dahmer's apartment.

If the police officers followed protocol, getting Dahmer's identification and running it through the database, they could have arrested him immediately on parole violations. Dahmer was a registered sex offender with three separate convictions from 1982, 1986, and 1989. In 1989, Dahmer was convicted of assaulting Sinthasomphone's older brother.

Meanwhile, Sinthasomphone's parents filed a missing person's report and gave his photo to another police officer. If they ran Sinthasomphone's description through the dispatch, he would have matched the missing person listed on the police report. They didn't do either.

Once they got to the apartment, Dahmer invited the officers. In the bedroom, Dahmer had a half-rotting corpse of his previous victim. He showed the officers pictures of Sinthasomphone in his underwear. The officers convinced that Sinthasomphone was Dahmer's intoxicated adult boyfriend from China, abandoned him inside of Dahmer's apartment. The police told Dahmer and Sinthasomphone to have a good night and quietly locked the door on the way out.

Later that night, as they continued their beat, the officers spoke over the radio. The first officer said, "Intoxicated Asian naked male (laughter) was returned to his sober boyfriend (laughter)."

The second replied, "I'm gonna get deloused back at the (police) station."

While the police enjoyed themselves with homophobic jokes, Jeffrey Dahmer injected hydrochloric acid into Sinthasomphone's cranium. This time, it was lethal enough to kill him. Dahmer decapitated Sinthasomphone's head and stored it inside the freezer.

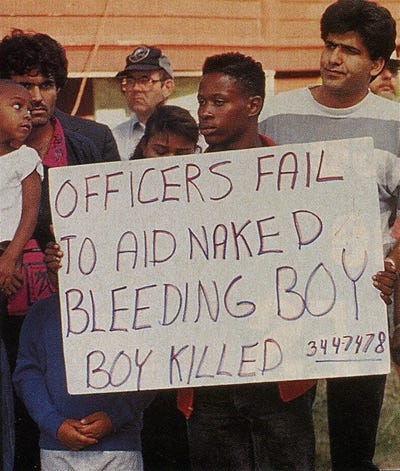

While these officers were initially fired amidst community outrage and protests. However, they were both reinstated into the police force after they appealed.

John Balcerzak retired in 2017 with full pay.

absolutely disgusting